I have read that a raccoon will wash a perfectly clean food item in filthy water before consuming it as a matter of genetically-based behavior. The inclination to rinse food prior to eating it must have historically served as an evolutionary advantage, even if in some circumstances it may harm the raccoon.

In a similar vein, I hail from a pathological lineage of collectors. My maternal grandfather collected and sorted stamps, which he sorted with care into enormous volumes made for that express purpose by societies of like-minded philatelists.

My father's collections include carved ironwood sculptures from rural Mexico; soapstone etchings from South Africa; small chrome timepieces that can be found in any Chinatown tourist shop; paintings of rural landscapes from his native Cuba; and colorful solar-powered yard lights that recreate Disney's Main Street Electrical Parade nightly.

I have collected old film cameras and 8mm film videocameras from back when home movies did not have sound; books by the beat writer Richard Brautigan; Ethiopian ceremonial crosses; and most recently, books on the history of medicine. The latter collection at one point approached a hundred books, which a sincere desire to live leaner has led me to pare down to the 15 volumes I found most meaningful and important.

The jewel of my remaining collection is a book called Occupational Marks by the dermatologist Franchesco Ronchese, MD. Published in 1948, it is the sort of dusty, leatherbound volume that invites a rich glimpse of a bygone era.

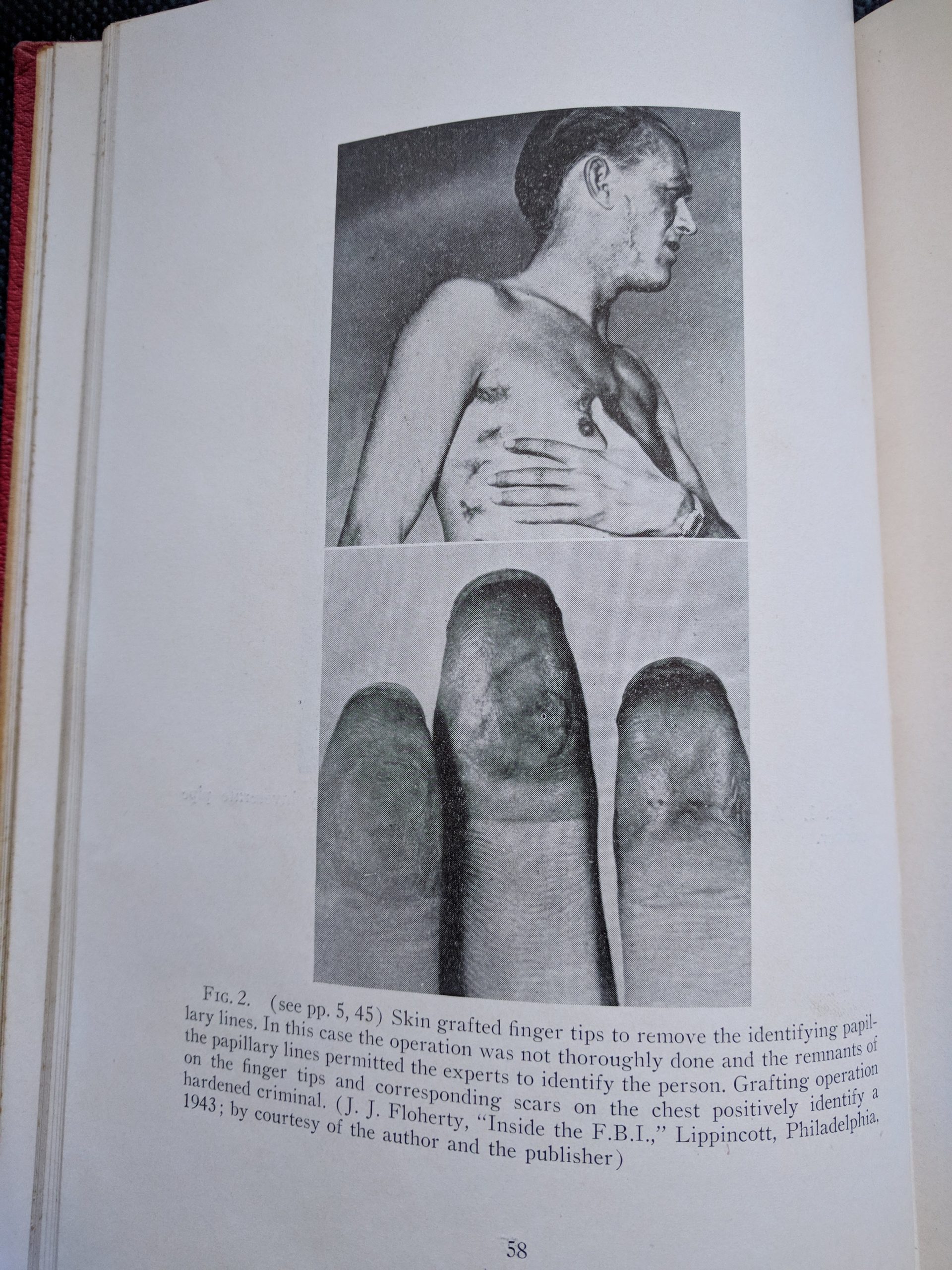

In the introduction and preface, there is an anecdote about a trauma surgeon the author studied under during his internship. Called upon to identify patients who were unconscious or had no identification, the surgeon would carefully inspect the hands for telltale calluses that might indicate what were delightfully termed the "stigmata of occupation." This had far-reaching consequences, even when the patient did not survive, since correctly identifying a body might mean securing a veteran's pension for the surviving spouse.

There are amusing sections highlighting how a careful review of an individual's hands or lips might distinguish between professional tuba, trumpet and trombone players.

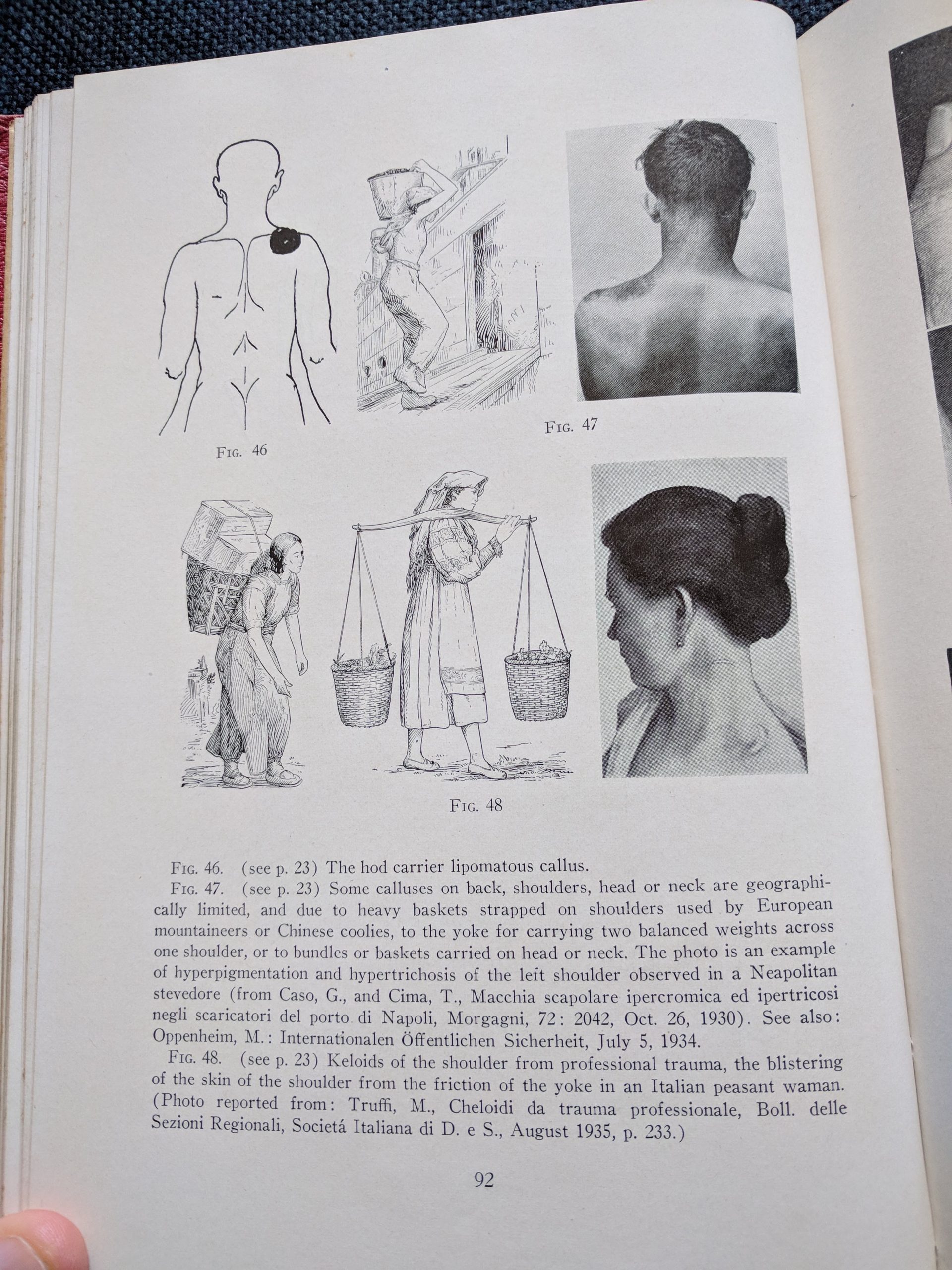

To turn the pages is also to see livelihoods from a prior century that no longer exist:

- artificial flower maker

- silverware maker who forces knife blades into silver handles

- spectacle frame polisher

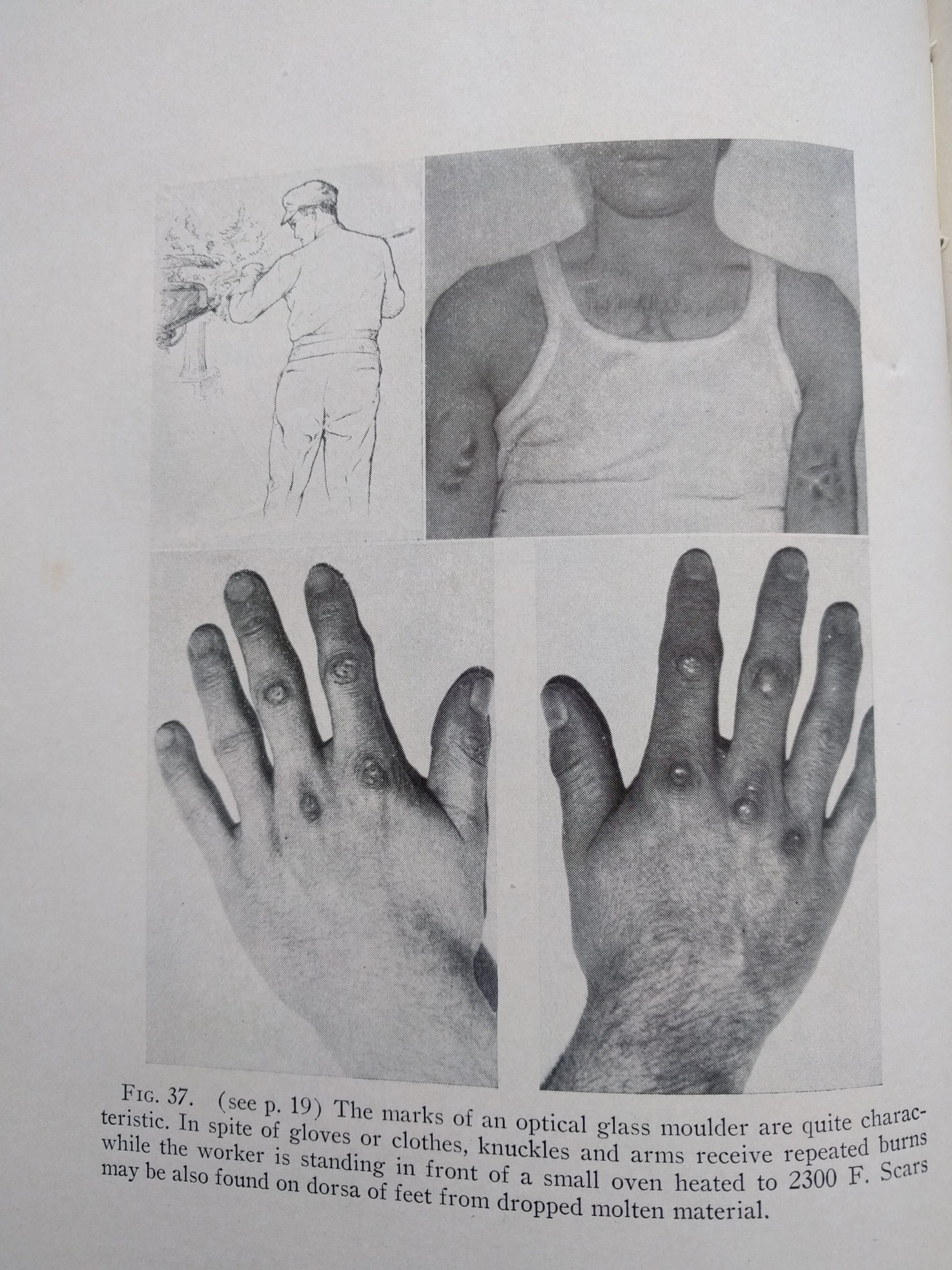

- optical glass molder

- boat caulker

It's enlightening to realize that craftsmanship and a deep mastery of skills once flourished. I am reminded of an oft-repeated quote from Robert Heinlein:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyse a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

This is the sort of quote that takes me by the lapels and shakes some sense into me - life is short, and there is so much to learn and do beyond the confines of the practice of medicine.

Has a high income and meaningful work hoodwinked us into believing we ought to spend our lives as super-specialized insects?

While a physician's job does not involve manual labor, we carry our own invisible "stigmata of occupation."

Has being a doctor left you with occupational marks you'd rather not have?

Comments 3

There are yottabytes of information available for free or near free. The only stigmata is myopic focus. I was trading commodities in 1976 when I was 24. We home schooled our kids through high school and by the time they were ready for college they already had 2 years of college completed. I ran 2 anesthesia practices and a pain practice. There’s plenty of stuff to learn about that pays.

In the gaming world there is developing a blockchain/etherium based kind of ownership where you may but a bullet proof vest and a hand gun and a AR-15 using ETH and have those items in you block chain wallet and be able to transport these items from game to game. You’ll be able to sell them on a market place, maybe become a manufacturer, maybe become a miner or provide commodities or become a bank or maybe a casino. Since ETH has built in contracts a transaction is secure transparent and permanent once the contract is fulfilled.

Can it work? Does blogo-land make some people wealthy? There are a million things to do. ETH crashed over Thanksgiving, got down to $486 so I bought some. ETH trades 24/7. Today it’s $615. Always something to do.

My father collected stamps before he passed away in the mid 80s. I inherited dozens of albums from him, mainly first day covers from the 50s-early 80s.

I actually was disappointed to find out that they are really not worth much. They are beautiful to look at but take up a ton of space. I was a coin collector myself. My daughter is not interested in either so the collections will likely not survive another generation.

Author

My parents and mother-in-law have large spaces filled to the brim with stuff. A friend makes her living decluttering the lives of older clients to prepare them for downsizing or moving to retirement homes.

My take home lesson is that I need to eliminate stuff and reduce the space I occupy once my kids are out of the house in order to ensure I never curse them with having to dump it all. Part of my retirement plan will include a built-in mourning period for parting with stuff.